Tuesday, March 28th, 2017

The Mosocophoros, Kriophoros and Early Christian Art

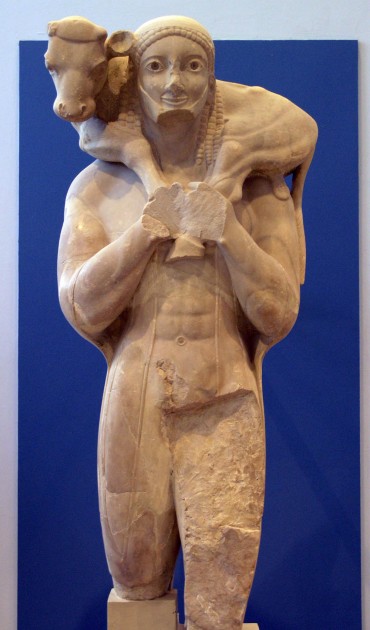

Moscophoros (Calf-Bearer), c. 550 BCE. Marble, height 165 cm (65 inches). Acropolis Museum, Althens. Image courtesy Wikipedia via user Marsyas.

When I was an undergraduate, I remember my professor casually mentioned that Early Christian imagery of Christ as the Good Shepherd was adopted syncretically from previous Greco-Roman images of a human figure who carries a sacrificial animal on its shoulders. She mentioned this point in passing when we were learning about the Moscophoros (or “Calf-Bearer,” shown above), but didn’t elaborate further. Had I asked for more details, I’m sure that she would have then explained that the Moscophoros from the Acropolis Museum couldn’t directly have influenced this Early Christian tradition (since this Moscophoros was buried under the Athenian acropolis from the 5th century BCE until the 19th century, thereby “missing out” on the Early Christian period). Instead, she must have been thinking of similar imagery found in depictions of Kriophoroi (“Ram-Bearer”) images from ancient Greece and Rome.

The Kriophoros depicts a shepherd or Hermes (specifically Hermes Kriophoros, due to an ancient tradition that Hermes carried a sacrificial lamb in order to prevent a plague in Tanagra). The Kriophoros imagery appears in a votive or commemorative context, specifically one which involves the solemn animal sacrifice a ram. Therefore, the kriophoros often can be seen as one who presents a sacrificial ram to a god or goddess. In other contexts, the kriophoros appears within pastoral imagery, and sometimes is seen as part of the imagery for the months or seasons, such as March or April.1 One such example is a Byzantine mosaic from Thebes Chalkis, which was highlighted in the 2012 exhibition Transition to Christianity: Art of Late Antiquity, 3rd – 7th Century AD as an example of the Kriophoros as a personification of April. 2

Not all Kriophoroi depict a figure carrying a ram over the shoulders, for the ram can also be held in figure’s the arms). However, many of them do follow the same composition with the ram being held on the shoulders, behind the neck of the male figure.

Late Roman marble copy of the Kriophoros of Kalamis, first half of the fifth century CE. Rome, Museo Barracco

Here are a few other examples of ram-over-the-shoulder Greco-Roman kriophoroi:

- Kriophoros Statuette, Archaic Period, Crete. The Cleveland Museum of Art believes that this is an unusual example which shows the kriophoros also as a warrior.

- Limestone Ram-Bearer, 2nd quarter of the 6th century BCE, from Kourion, sanctuary of Apollo Hylates

- Limestone Hermes, ram-bearer Cypriot Archaic 6th century BC

- Hermes Kriophoros – circa 5th century BC, at the Archeological Nusem, Palermo

- Hermes Terracotta statuette, known as “Hermes Criophore,” from ancient Thebes in Attica. C 500-450 BCE, at the Louvre Museum

In the 3rd and 4th centuries, Early Christians adopted this imagery. However, it seems that the imagery was syncretic, meaning that the Early Christians gave the kriophoros imagery new meaning. Instead of functioning as a representation of a votive figure or an ordinary shepherd, Christians used the Kriophoros to depict Christ as a protective figure who will care for his followers (his “flock”).

Apart from the parable of the Good Shepherd that appears in the Gospel of Matthew and Gospel of Luke (New Testament), it is likely that Christians also were inspired to draw on shepherd imagery due to the Christian text, The Shepherd of Hermas written sometime around the early-to-mid 2nd century. In this text, a freed slave named Hermas is the recipient of heavenly messages, and he is guided and taught by a heavenly messenger who is dressed as a shepherd.

Such a protective figure was no doubt appealing to the Early Christians, who were persecuted heavily before the Edict of Milan in 313 CE. With such syncretic imagery too, the reference to Christ could easily be overlooked by a Roman who was accustomed to seeing the Kriophoros in art.

Here are a few other examples of Good Shepherd imagery influenced by kriophoroi:

- Early Sassanian Kriophoros (Good Shepherd), 3rd-4th century CE from the British Museum

- Sarcophagus fragment with the Good Shepherd, early 4th century

- Trapezophoron (table leg) with the Good Shepherd, mid 4th century, at Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture

Do you know of other good examples of Kriophoroi, either Greco-Roman or Early Christian?

1 David W. Jorgensen, Treasure Hidden in a Field: Early Christian Reception of the Gospel of Matthew (Berlin: Walter De Gruyter Inc), 2016, p. 124. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=8ucsDQAAQBAJ&lpg=PT124&ots=I7nta1T9eL&dq=kriophoros%20pastoral&pg=PT124#v=onepage&q&f=false

2 Anastasia Lazaridou, Transition to Christianity: Art of Late Antiquity, 3rd – 7th Century AD. New York : Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation, 2011, p. 96. Text available online: https://issuu.com/cdedegikas/docs/transition/96

M:

Thanks for a very informative post. From my study of Venetian Renaissance art I know that what we have today is only a small fraction of what was produced by the artists. I suspect that the images you reproduce in this post must have been ubiquitous in the ancient world.

Five centuries is a long time and Moscophoros must have been influenced by others and in turn influenced many others before being buried.

Frank

Hi Frank! Thanks for your comment! Yes, I think that these images were ubiquitous in ancient times. And you also raise a good point about the Moscophoros. It was created around the middle of the 6th century, so it definitely was around for about a hundred years before it was buried in the 5th century. That sculpture definitely could have helped take part in spreading the moscophoros/kriophoros imagery before its burial.

You might find this interesting. It’s an article about a recently discovered kriophoros ring that was found in the harbor of Caesarea Maritima. I don’t think it’s early Christian art or if it is, it’s syncretistic. I think it’s from the third century since there are some coins from that era as well. Thanks for your nice blog.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-59754153